This website aims to educate, that’s true. But what better way to learn than through a crazy, entertaining story? That is what I have for you today.

Remember Negative Oil Futures?

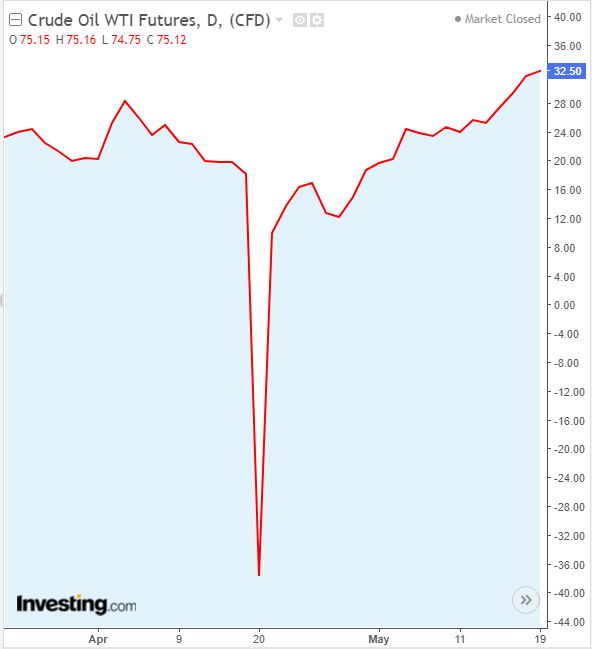

The story hinges on an interesting phenomenon which occurred on April 20, 2020 – AKA 4/20 2020. Certain Oil Futures, contracts to buy/sell oil barrels at a future date, actually went negative for the first time ever. If you don’t understand what they means, it simply means this: you could get paid to buy oil!

Crazy right? People were getting paid for something that you should have to pay for. But why… and how? That is where the experts can help us out.

How is That Possible?

Reuters explains that the futures under question, West Texas Intermediate futures, are actually a binding contract. It is not just some computer ticker, or symbol on a screen. When you enter into a WTI futures contract, you are contracting to accept 1000 barrels of crude oil in Cushing, Texas on the expiry date. If you are unable to store the delivery of oil, the contract carries a harsh “storage fee” penalty.

The problem was that Cushing, Texas was out of storage! Many people were left holding contracts for oil which they had no way to store. And the benchmark contract, the one you see on the chart? It expired the very next day.

Unprepared to accept 1000s of barrels of oil the very next day, nervous traders scrambled out of their positions as fast as possible. To avoid harsh “storage” penalties, they were willing to actually pay to get rid of the obligation to have oil delivered to them.

Thus, buyers were paid to accept the oil. Simple enough, right?

But wait, it gets more interesting.

Enter: The British

According to the media reports, there were nine of them. Nine English traders who operated out of a picturesque town called Theydon Bois in the country of Essex. Their company name was “Vega Capital”.

This short Bloomberg documentary highlights the fact that, although these traders were well off, they weren’t exactly like other traders. These guys made their own way in the world, starting from modest blue-collar, working class backgrounds. At least one of these traders was pushing shopping carts for a living up until a few years ago.

That makes what is to come all the more interesting.

Payday

It was the morning of April 20, 2020. The traders at Vega Capital had a plan.

According to them, the market was giving signals that Oil Futures were going to fall. They planned to capitalize on this fall. Probably the most potent signal was the exchange telling people that it is possible for oil futures to go negative, and preparing brokers for that possibility.

Either way, they had made up their minds: Benchmark WTI Oil Futures were going to fall, and they were going to make money off of it.

How Did They Do It?

There were three main parts. Well – maybe more… but let’s keep it simple:

Part 1: Agree to Trade at Settlement

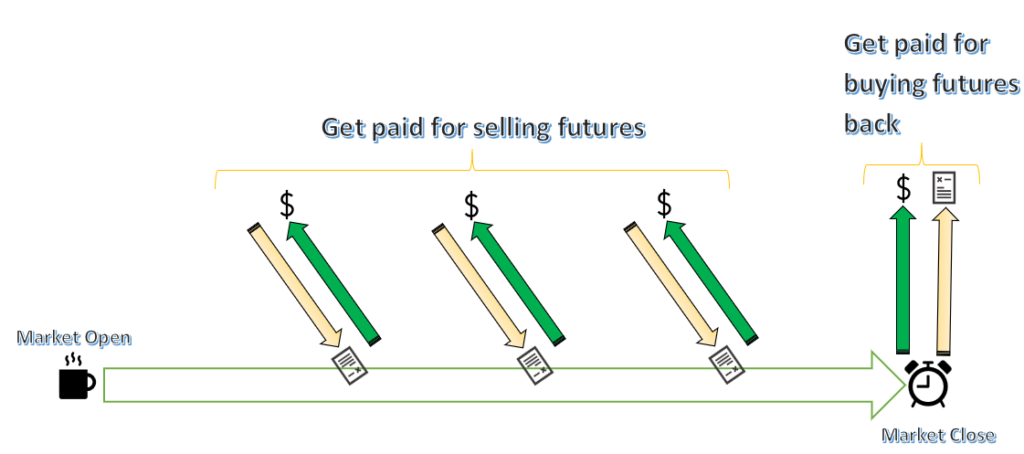

The first thing these traders did that morning of April 20 was agree to “Trade at Settlement” with a third party.

“Settlement” refers to the closing price at the end of the day. Therefore, “Trade at Settlement” is an agreement made between two parties that they will trade futures at the market close (end of day), whatever the price is at that time.

Part 2: Short Futures (Sell Futures)

As you might know, “being short” means that you are betting on a price decline.

In the case of futures contracts, the way to “be short” is to simply sell the futures. That is exactly what these Essex traders did. During the day, the Essex traders sold a significant amount of oil futures. In fact, they were among the largest sellers in the entire market. The amount which they sold was equivalent to the amount which they had contracted to buy later (see Part 1).

While they were selling these futures they collected a fee (the price of the futures). They were essentially betting that what they were being paid for these futures now (ie. the market price) was more than what they would have to pay to buy them back later.

Part 3: Offset Trade

The final thing which these traders did was an offset trade. All that this means is that they bought an amount of oil futures equivalent to the amount which they sold during the day. It is called offset because it eliminates any obligations to actually deliver oil or receive oil.

Fortunately for the traders, they were right about the direction that the futures were heading. The price which they sold the futures at was higher than it was at settlement. In fact, since the settlement (ie. end-of-day) price of these oil futures was negative, meaning they were paid to buy these futures! They were paid almost $38 a barrel!

The party with which they performed the offset trade with was the same party that had agreed to the TAS agreement (Part 1) in the morning. This means that they really didn’t have a choice but to perform the trade. This TAS agreement acted as a sort of insurance policy incase no one wanted to sell to them at the end of the day.

Profit & Controversy

At the end of April 20, 2020, the nine Essex traders had made about $660 million altogether. Not bad for a single days work. It was a trade which was almost too good to be true. They were paid on the sell side and on the buy side of the trade!

Unfortunately for them however, questions abound about the legality of these April 20 trades. Did they intentionally push the settlement price down by flooding the market with orders, called “banging the close”? It appears at least one lawsuit has been filed against the group.

The traders have decided to lay low for a while. Apparently when a reporter called one of them to inquire about the trade, the trader simply said “Sorry, I can’t hear you over the sound of my yacht!“.

As for what the future holds for these traders, who knows. But I don’t think any of them will be returning to pushing shopping carts anytime soon.

Happy Investing.